Gitxaała Nation is going to the B.C. Court of Appeal to challenge the lower court’s decisions in regard to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). It’s a crucial appeal for Indigenous rights in B.C. A success for Gitxaała could help advance Indigenous rights under UNDRIP in other courts across the country, creating widespread change for future generations. Let’s dive a bit deeper into Gitxaała Nation’s case to better understand exactly what’s at stake.

Facts

Gitxaała Nation went to the BC Supreme Court in April 2023. You may remember the upswell of support in their movement for mining justice – RAVEN raised a whopping $240,000 during the hearing, helping Gitxaała Nation to access the legal system.

Gitxaała’s case, heard alongside Ehattesaht First Nation’s case, led to a monumental win for their mining rights in B.C.. Justice Ross ruled that granting mineral rights to third parties on First Nations territories triggered the duty to consult and accommodate (DCA). In order to protect Aboriginal rights affirmed in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, B.C. is required to uphold the DCA whenever a First Nation’s rights may be affected by a government action, such as granting a mineral claim on a First Nation’s territory. B.C.’s mineral tenure system does not even notify First Nations when an online claim for minerals is staked on their territory, let alone require consultation or consent, making it a clear violation of the DCA.

B.C. is now required to create a new framework for the mineral claims process that fulfills the DCA. This decision gives over 200 First Nations more say over how, when, and where mining occurs on their territories and helps support Indigenous-led cases in Ontario and Quebec over their respective mineral tenure systems that are similar to B.C.’s.

This is an incredible precedent that furthers mining justice for First Nations, but Gitxaała Nation also argued that B.C.’s mineral tenure system is inconsistent with UNDRIP, itself part of B.C. law through the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA). The mineral tenure system doesn’t consult with First Nations, so it certainly doesn’t provide the free, prior and informed consent required by UNDRIP.

However, the BC Supreme Court didn’t rule in favour of Gitxaała Nation on this point. Justice Ross found section 2(a) of DRIPA does not implement UNDRIP in B.C., and section 3 of DRIPA isn’t justiciable – in other words, a First Nation can’t go to court and get a ruling that a B.C. law is inconsistent with UNDRIP. This decision makes DRIPA simply a political promise, or vacuous political bromide, that holds no legal accountability for the province to implement.

This new precedent has already been seen in other Indigenous-led cases in Canada. For example, Kebaowek First Nation went to the Federal Court of Canada with RAVEN’s support, arguing they have the right to free, prior, and informed consent around nuclear waste projects under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA), which is the federal government’s version of implementing UNDRIP. Canada opposed Kebaowek in court with similar arguments as B.C.’s lawyers did in Gitxaała’s case. They cited Gitxaała Nation’s case and Justice Ross’ decision, giving it more credibility.

This makes Gitxaała Nation’s appeal that much more important.

The Appeal

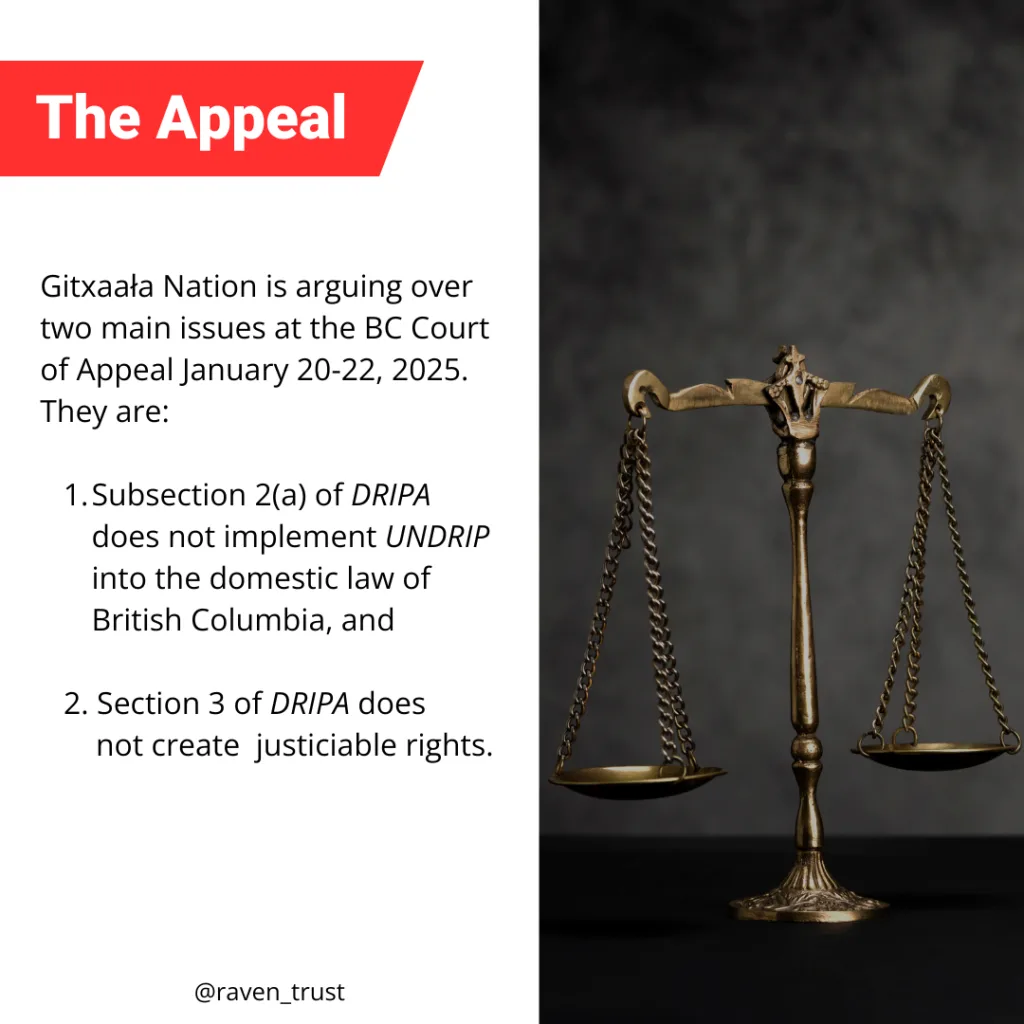

Gitxaała Nation is appealing on two main issues at the B.C. Court of Appeal this January 20th, 21st, and 22nd. They are:

- Subsection 2(a) of DRIPA does not implement UNDRIP into the domestic law of British Columbia, and

- Section 3 of DRIPA does not create justiciable rights.

Gitxaała wants to overturn these rulings with new declarations from the appellate court. More specifically, they want (a) the Court to make it clear that UNDRIP applies to all laws in B.C., including judge-made laws (i.e. the common law), and (b) under section 3 of DRIPA, there is a justiciable right to bring a court action to hold B.C. legally accountable for ensuring laws are consistent with UNDRIP. The latter declaration could see an entire overhaul of the mineral claims process as it is inconsistent with UNDRIP, potentially requiring the Province to need the free, prior, and informed consent of Gitxaała Nation.

The new mineral claims framework that B.C. is currently drafting because of Gitxaała’s lower court ruling focuses only on the bare minimum of the duty to consult and accommodate (DCA), rather than aligning with UNDRIP. While B.C. has promised to reform the Mineral Tenure Act at a future date, they did so only after Gitxaała Nation filed their case. Without the present appeal, this type of legal challenge won’t be available to Indigenous Peoples in the future.

How will this change rights for Indigenous Peoples in B.C.?

Section 3 of DRIPA requires B.C. to make its laws consistent with UNDRIP, but unless Indigenous Peoples can seek relief in court when there’s a dispute over whether a law is consistent with UNDRIP, DRIPA under section 3 will not have “teeth.” First Nations in B.C. would not be able to take the Province to court when B.C.’s laws are inconsistent with DRIPA.

If the appellate court rules in favour with Gitxaała’s arguments around section 2(a), then laws passed by the legislature and judge-made laws, including the DCA and potentially, the tests for Aboriginal rights and title developed by judges interpreting s. 35 of the Constitution Act, would have to be consistent with UNDRIP. In Quebec, a trial-level decision already reformed the “Van der Peet” test for Aboriginal rights that freezes Indigenous societies at a “magic moment” in time just before European contact to be consistent with UNDRIP. Gitxaała Nation is seeking something similar in their appeal to this trial-level decision.

UNDRIP has several articles that would advance Indigenous rights much further beyond the status quo of Indigenous rights in B.C., particularly around free, prior, and informed consent and environmental protection. It lists significant advancements in a number of factors, including the following: self-determination; economic, social, and political rights; cultural preservation; spiritual rights; language revitalization; combating prejudice and discrimination toward Indigenous Peoples; appropriate social services and housing; land rights, including the conservation of medicinal plants, animals, and minerals; and more. Applying UNDRIP to all laws, including the common law, would bring systemic change for Indigenous rights in B.C..

Conclusion

UNDRIP is an international mechanism for nations to use to uphold Indigenous rights around the world. When it was first presented in 2007 at the United Nations, only four countries initially refused to sign on – Canada was one of them.

B.C. passed DRIPA stating they would become a leader for honouring and respecting Indigenous rights. Even the province’s lawyers for this appeal have written that “Canada—and within it, B.C.—has emerged as a world leader in UNDRIP implementation”

Yet, even after the Action Plan was released for DRIPA (promising to “Modernize the Mineral Tenure Act in consultation and cooperation with First Nations and First Nations Organizations”), B.C.’s lawyers continued to completely oppose Gitxaała’s legal arguments that the colonial relic of a mineral tenure system was inconsistent with UNDRIP and that DRIPA created justiciable rights for Indigenous Peoples in B.C.. Three years later, after Gitxaała has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on legal fees to say their rights under DRIPA and UNDRIP go further, the province continues to oppose the Nation.

B.C. needs to be held accountable, not just by Indigenous Nations and the general public – they need to be held accountable to DRIPA under law. Without Nations being able to go to court for their rights under DRIPA, the province can get away with violating its very own act that is supposed to promote reconciliation. As history has shown us, it’s unlikely B.C. will uphold its agreement to DRIPA, making this appeal crucial for the future of Indigenous rights in B.C.

People all over B.C., Canada, and even the world will be waiting to see what happens with Gitxaała’s appeal. This precedent will affect many other Indigenous-led cases, in one way or the other. We hope that Gitxaała will be successful this January 20th, 21st, and 22nd.